Architecture and the Graphic Novel

Photo courtesy of Nick Sousanis, Spin, Weave, Cut

Originally published by WHY Architecture

WHY EYE: TOP 5 ARCHITECTURE GRAPHIC NOVELS

The form of the graphic novel is uniquely well suited to communicating ideas about architecture and urbanism. As a story built on a grid, the interlocking frames are structured like a building or a city; a premise which has inspired countless architectural manifestos and graphic biographies of key figures in design history. What better way to relate the machinations of New York’s City’s “master builder,” Robert Moses, or to reassess the legacy of the modernist designer Eileen Gray?

When you begin with a grid, you also have a framework for breaking the rules. Graphic novels have the capacity to accessibly express highly complex constructions, chronologies, and concepts; they reveal the multiple ways that a scene might be framed, and invite us to interpret the world through the eyes of others. Warning—when you start exploring the intersection of architecture and graphic novels, it’s a rabbit hole which is very hard to escape from. Here’s a selection of our top 5 to get you started:

WORDLESS WORLD

The City: A Vision in Woodcuts (1925) by Frans Masereel

Frans Masereel’s “wordless novel” of 100 woodcut prints is considered the originator of the graphic novel form. Instead of following a sequential plot, The City captures an anonymous metropolis from multiple angles—documenting daily encounters and archetypal events collaged from Masereel’s own experience living in Berlin, Geneva, and Paris. Scenes ranging from funerals to factory floors, prison cells to orchestra pits, are depicted in a strong graphic language which borrows from German Expressionism while remaining true to the traditional techniques of the woodcut. Each print is a frame unto itself, and together they form a way of reading the city—not as a series of clear connections, but a vision of disparate elements and stark oppositions. This is a vision which is inherently political—scenes of wealth and leisure are directly juxtaposed with those of poverty and pain, sharpening the reader’s awareness of the injustices which support the structure of the city. The book serves as a mirror for life today, riddled with the same tensions, contradictions, and generative energy.

CHILD’S PLAY

Playground of My Mind (2017) by Julia Jacquette

Simultaneously a memoir and an exploration of modernist playground design, Julia Jacquette’s Playground of My Mind imagines what cities might look like if children were given space to invent their own forms of play. The author’s 1970s childhood in New York’s Upper West Side is remembered through the lens of design; her father, an architect, teaches her to read the utopian principles of the Brutalist tower block where they live, and her mother’s sartorial appreciation for color and pattern informs the book’s visual vocabulary. Watching her father absorbed in the process of designing a playground, Jacquette realizes that work at its best is a form of “deep play”; that process is mapped back onto the experimental adventure playgrounds of New York City and the visionary designs of the Dutch architect Aldo Van Eyck. Cross-referencing theories of childhood development with personal impressions of the evolving city, Jacquette reflects on the ways we learn though play, and how our own possibilities for playfulness are defined by the built environment.

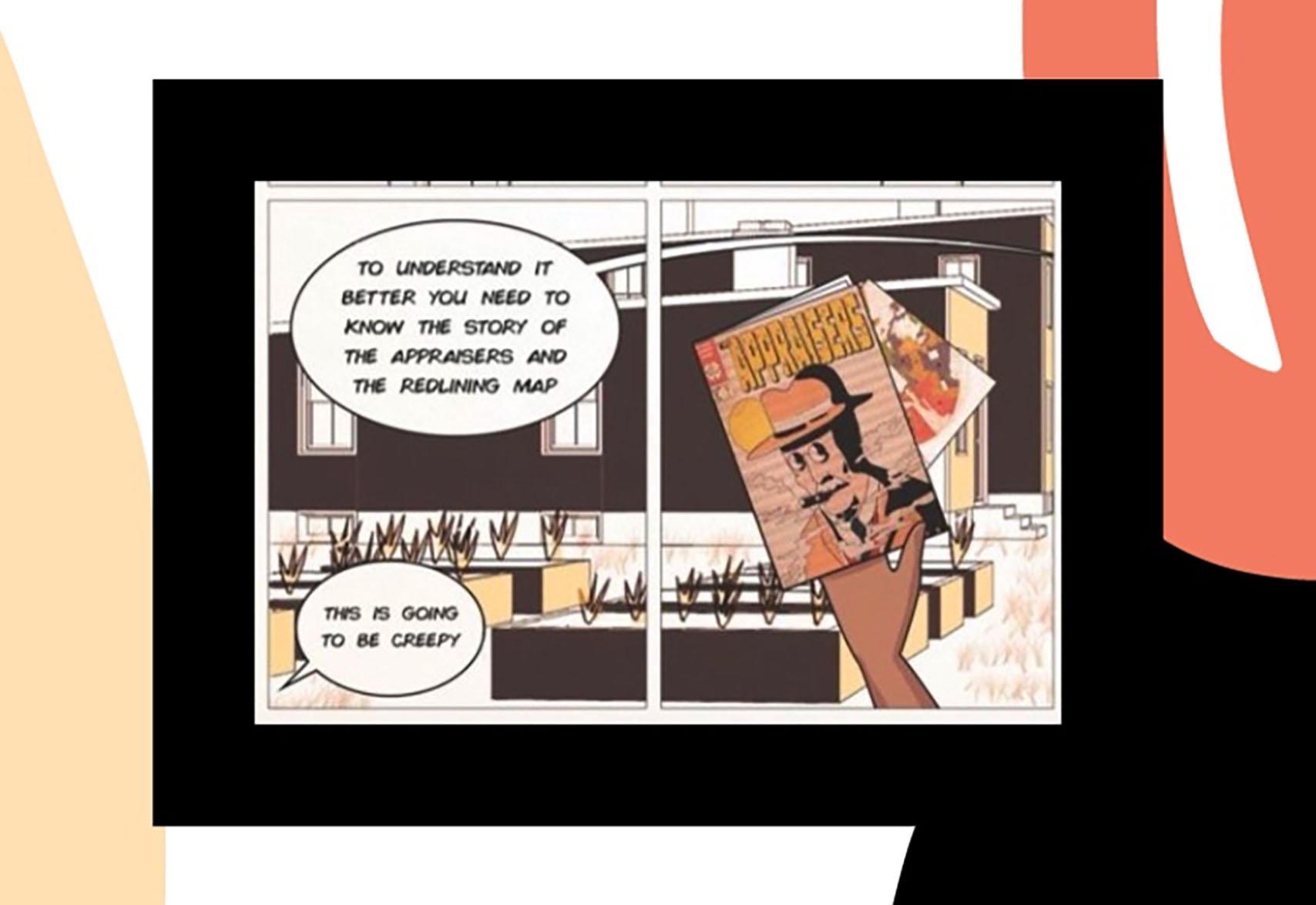

VISUALISING REDLINING

The Tracers (2016), Ruben Segovia

Graphic novel narratives have often been used to shed light on difficult truths, and Ruben Segovia’s documentation of redlining practices in St. Louis and Ferguson, MO, is a case in point. The phrase “redlining” is itself a way of visualizing the racist zoning policies which shaped American cities in the 20th century, and Segovia reapplies the idea of lines and borders to construct a frame-by-frame investigation of the region’s history of segregation. The Tracers opens with a scene of a vacant lot which once served as a backdrop for a notorious anti-integration pamphlet; we follow two African American teenagers as they expose the underlying structures which allow discrimination to persist. Racism, they discover, is built into the urban fabric, and policies supposedly abolished in the 20th century continue to impact the lives of communities today. The book was produced as part of a series of pedagogical experiments by Harvard design students, and it raises the question of how best to illuminate highly sensitive socio-political issues; as a form which is simultaneously accessible and complex, the graphic novel provides a powerful platform for communication and debate.

BEYOND THE BOX

Unflattening (2015) by Nick Sousanis

Graphic novelist and academic Nick Sousanis twist the graphic grid to reveal the complex interplay between text and image, exploring the networked ways that humans make sense of their surroundings. The book weaves together multiple ways of seeing borrowed from science, philosophy, art, literature, and mythology, and while Unflattening is not directly about architecture, its forms and metaphors are inherently architectural. Opening to an urban dystopia of boxes within boxes—zones where time, space, and experience are confined to four walls—Sousanis deconstructs the grid to allow us to read between the lines. Boxes split and spill into one another and the grid evolves into something that looks more like a forest or a root system than an urban metropolis. Described as “an insurrection against the fixed viewpoint,” Unflattening uses the collage-like capacity of the graphic novel to demonstrate that perception is always an active process of combining different vantage points; the reader is invited to enter a visual and verbal multiverse where it is possible to see past the boundaries of a fixed—or flat—state of mind. In this world, everything—the practice of architecture included—is dynamic, interrelated, and on its way to becoming something else.

PSYCHIC URBANISM

(童夢) Domu (1980) by Katsuhiro Otomo

Apartment buildings are the perfect setting for a story, bringing together multiple different lives under one roof and allowing for connections and differences to play out. By slicing through walls and opening up cross-sections, the graphic novel adds a new psychic dimension to apartment storytelling—an effect amplified by the structural genius of Katsuhiro Otomo, a master of narrative form and a keen observer of architecture and urban culture. Domu was inspired by the apartment complex where Otomo lived when he first moved to Tokyo, and the story follows a series of characters as they are influenced by mysterious supernatural forces. The attempted rationalism of the detectives is undercut by spatial and psychological breakdown, and the building holds the clues to the inhabitants’ emotional triggers and sites of trauma. Domu is simultaneously an addictive thriller and an architectural psychodrama, illuminating the ways that our lives and minds are shaped by the structures we inhabit.

Graphic novels reveal the ways that we actively “build” a narrative in the act of reading, combining different frames and types of information to make sense of what we see on the page. Likewise, when we walk through a well-designed building or green space, we are equipped with tools to understand our surroundings and creatively map our own path. The point is participation; a compelling story is generated when individuals have the agency to shape personal experience, working with the dynamic contours of a structure to assert their particular way of being in the world. A genius graphic novel might be modeled on an ideal building or a city, but what might happen if the practice of architecture was modeled on the freedom and flexibility of the graphic novel?

Originally published by WHY Architecture