Georgian Gothic in Marylebone

“I love the low – you can collect beautiful objects and have good taste, but there’s got to be a bit of low in there.” This statement is hard to square, coming from a man sitting in an antique Georgian chair in a room lit by gently scalloped Gothic windows. Tree ferns graze the glass from the courtyard outside, and the room has the feel of a church vestry – the type of place where a parson might carefully examine church records. The type of parson, that is, who might wear Nike Air Max sneakers and use 1970s Gucci letter openers. “They’re sort of tacky, really,” says Elliot, flipping the paper knife from its lizard-skin case, “but they struck a chord. If there’s anything that connects the way I think about objects and image making, it’s an obsession with detail and proportion.”

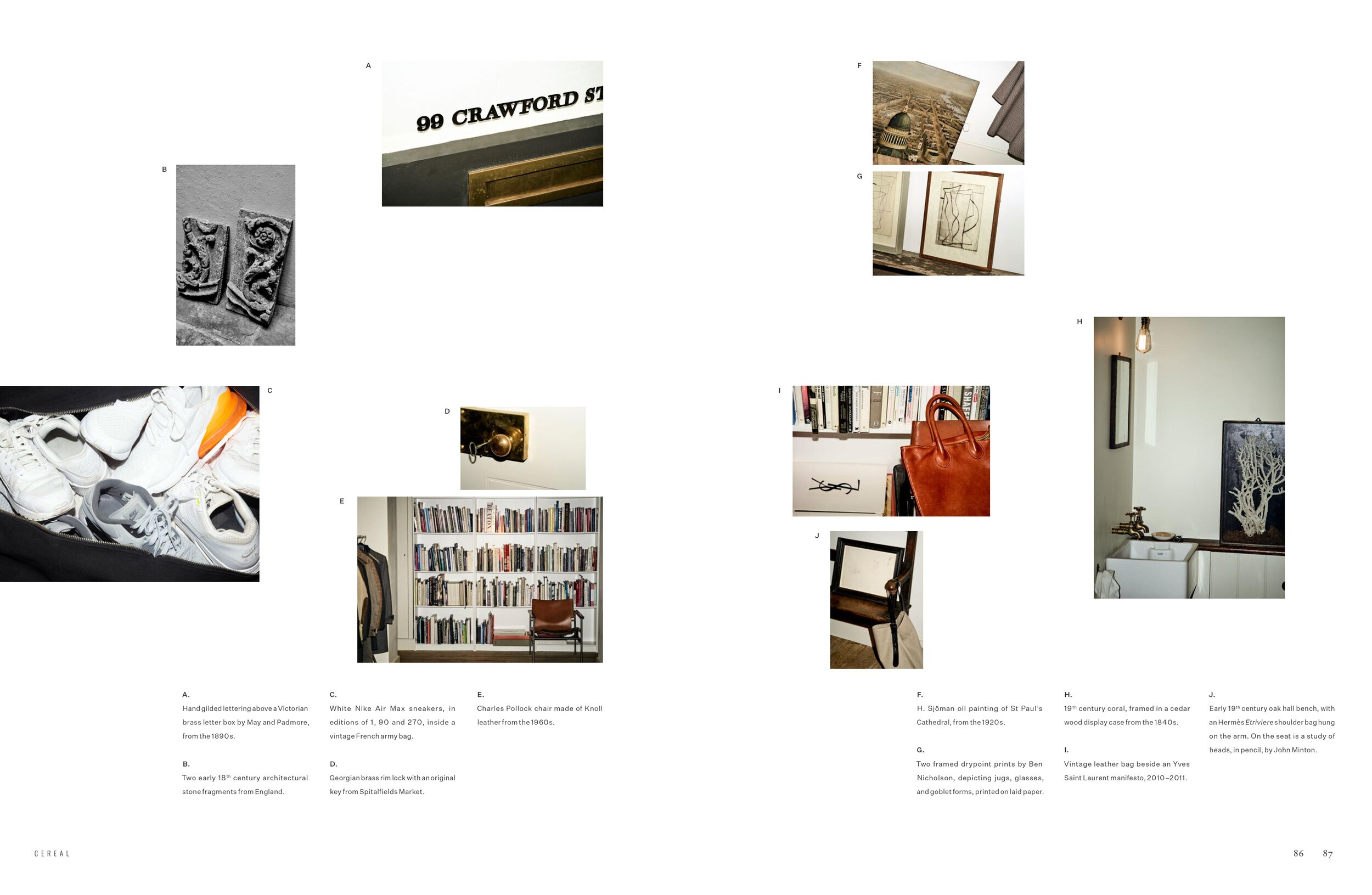

Attention to form, material, story, provenance – these are the factors which unite the idiosyncratically arranged objects in Elliott’s Marylebone studio. “The building was constructed in the late 18th century, it looks like it was originally some kind of store. When I first visited, I thought, ‘What do I need with a shopfront?’ But I was sold on the Gothic windows: suddenly I had a sense of what the space could become.” He walks to an exposed fireplace, bright Hermès boxes lighting up the empty hearth. “We discovered the fireplaces when we started stripping back – I thought I’d give the place a lick of paint then ended up ripping it apart. Downstairs we found all these clay pipes, jars, ceramic dogs, old shaving creams – I kept conjuring romantic notions about what the building might have been.”

It is perhaps important, at this stage, to clarify the details of Elliott’s own provenance and profession – in the same way as one might cite the particulars of the Regency sofa by the front entrance, upholstered in hand-stitched horsetail and hessian. Or the mahogany Klismos chair of the same era, with the curved back and foliate-carved legs. Or the Franco Albini midcentury bookcase. Or the George III library table, with the red leather hide-top and adjustable ratcheting writing slope.

But it is foolish to pin any label or definition to Elliott’s practice. He describes himself with the sweeping obliqueness of a polymath: “I would say I’m a creative consultant. What I do in fashion is a bit of everything – a bit of design, styling, putting an image together, branding... I don’t view the different parts in isolation. I’ll be consulting on the brand, and I’ll see a dress being made and I’ll say: ‘Could you make the sleeve a bit longer?’ It’s all part of the same story.”

In an industry beset by celebrity, Elliott defends his privacy fiercely. Rather than reeling off a list of his clients, he lets the creative impact speak for itself, and although he’s a compulsive image-maker, you won’t find him on Instagram. It’s enough to say that he worked closely with Christopher Bailey at Burberry during the 17 years that the brand underwent its reinvention. Designers come to Elliott for his freewheeling capacity to make aesthetic connections: “I think the desire to arrange and combine, to generate parallels and proportion, is intuitive. You see it in Sir John Soane's Museum – I love the basement the most. The interior of the kitchen is reduced to the essentials, but there are still layers of detail in the joinery and the beading. And, of course, in the rest of the house, there are all the combinations of furniture and archeological fragments.”

The word ‘combine’ carries with it the implication of storytelling. In Italian, the verb combinare implies not only arrangement, but also plotting and strategy – all highly applicable to the art of branding. But a story only resonates if it is true to life, and, for Elliott, relevance is everything: “What I do has a pragmatism to it – it’s about anchoring creativity to some aspect of reality, tuning brands into what they know they are and should be. Pinpointing that relevance takes research, and, for me, it always starts with an image of some kind. Whether the image is in here,” he says, tapping his forehead, “or from a book or a magazine, it’s something that suggests a particular feeling or atmosphere.”

“I’ll often come to the studio in the morning with an image in mind, and we’ll use it as a starting point to find other references and connections. What I’m looking for can’t usually be found online. Instead, I’ll look through my archive of magazines and books, or call up antique dealers to see if they have anything that fits – I might be thinking about Regency ironmongers’ fastenings, or 1970s car interiors. We build with those elements. Rather than working digitally, we photocopy images and start tearing them up, combining them on the floor with vintage pieces and found objects. We’ll take that initial image or idea, and work outwards to create a whole world around it.”

“I like to use the word ‘pottering’ – that’s what I’d say I do, whether it’s arranging stuff at home, or researching the context of an object that’s caught my imagination.” He opens the drawer of an oak library table, revealing splashes of wax hardened into the grain. “I used to collect 20th century furniture, but there’s something about provincial Georgian furniture that seems truer to the contemporary. There’s a simplicity and functionality to the design, but you also get layers and embellishments. Like these brass rim locks on the doors, for instance – I buy the old keys from Spitalfields Market, and get the ends recast. I’ve been obsessed with porphyry recently, and Grand Tour souvenirs, like these marble models of Roman baths. Maybe I’ll fill the studio with 19th century taps and bathroom fixtures – I’m fascinated by the engineering.”

Alongside his work as a consultant, Elliott occasionally designs interiors for friends. He is also considering the possibility of opening his studio as a gallery, though for now, the shopwindow remains screened by a grey blind. The gallery would serve as a distillation of the creative process: “Downstairs it’s very much a working space, with vintage items, clothes, magazine archives – bits for me and the team to pick out and show to clients – but the shopfront upstairs would be a place for us to put the things we love, changing them around on a regular basis.”

Books are arranged on the George III table and the Albini shelves; delicately twisted branches of coral are placed next to a monograph on Margiela, and two Ben Nicholson lithographs lean against the wall. I notice how the grimacing profiles of Gilbert and George echo the expression of the bronze head on a plinth. “That’s Seneca, supposedly. He’s an 18th century copy of a Roman bust from Herculaneum. Do you think it’s too much?” Possibly. But even as the whites of the Stoic’s eyes threaten to topple the arrangement into bathos, the no-nonsense posture of the hessian sofa pulls the atmosphere back to sincerity. It’s a fine balance, a high-wire tuning of gravitas and melodrama. But it works.

“I think part of me is drawn to the extravagance of a John Soane or a Horace Walpole, but the joy comes in restraint – stepping back and thinking about how different elements work together. Cutting, layering, building – everything’s in the editing. That’s one of the reasons I don’t generally collect visual art, though I did recently buy a painting from the school of Jusepe de Ribera. For the most part, if I got a painting back to my house, I’d probably want to adjust the colour or composition to make it fit. It’s the same when I enter a room and feel that the width of an archway is off, or the beading on a panel is a couple of millimetres too thick. I don’t claim to be an expert – I’m just a very visual person. When you look at something long enough – whether it’s the texture of a paint finish or the fitting of a window – you start to learn its vocabulary.”

It all comes down to looking – and that’s something about Elliott that sets him apart. At the same time as he works into an image, by editing and shaping it, he works outwards, reaching for the network of visual connections that locates the image in the real world. In doing so, context is not so much found as created: to tap into the Zeitgeist means to define it.

The trick is not to know what you’re looking for and, for Elliott, looking is a way of life. It is the bronze-green paint of 18th century shopfronts, and the football scarves on the Circle Line. It is the shape of wrought iron railings, and the fold of a lapel. “We feed off these things, and they filter into different parts of life without realising it. It’s all part of the same process.”