An interview with artist Edmund de Waal

It is early morning in Los Angeles. The sky is resistant – orange-grey – ashy remnants of a sun which rose too large, and red, and disappeared. It is wildfire season in California. A short drive east – fires gasping and breaking over the San Gabriel Mountains, unseen in Mid-City where the air holds the heat and offers it up for breathing.

I have been thinking about London, home, and the fire which shaped the city all those centuries ago. Fire which sounded itself as a deafening roar, consuming and rippling over rooftops and spires like a curtain closing to applause. In Los Angeles, the traffic silences what is here to be heard. And now this strange, frictioned line from here to home, because this morning I have the chance to speak with an artist whose practice is an oscillation between worlds. Edmund de Waal’s art can be read as an expression of stillness; silent vessels contained within a shared logic of reticence and restraint. And yet that stillness is also the surfacing of constant motion, bearing witness to exile and migration, place and remaking – to the patterns of being which shape each life in relation to another.

De Waal is in his studio in South London, and I ask about the weather outside. “It’s very golden,” he says. “Four in the afternoon, the beginning of autumn – the studio is an almost empty room and the light just falls down through the skylights. It’s a light box.”

Light enters and forms the space as De Waal tells me about the objects that surround him. “On the desk in front of me are 70 or so books about Paris, and there are pieces of English alabaster from Nottingham; in the Middle Ages, English alabaster was regularly sourced to carve devotional statues but now there’s only one last quarry still in use. There are fragments of the radiant Hornton stone which I’ve used for a series of benches, and thin fragments of porcelain which I’ve inscribed with lines of Chinese poetry and layered with gold leaf. I have a tea bowl made in Meissen in 1712, pure as anything, and a Buddhist sculpture of a hand with long, long fingers – bronze – you can hear it, I’m picking it up now.”

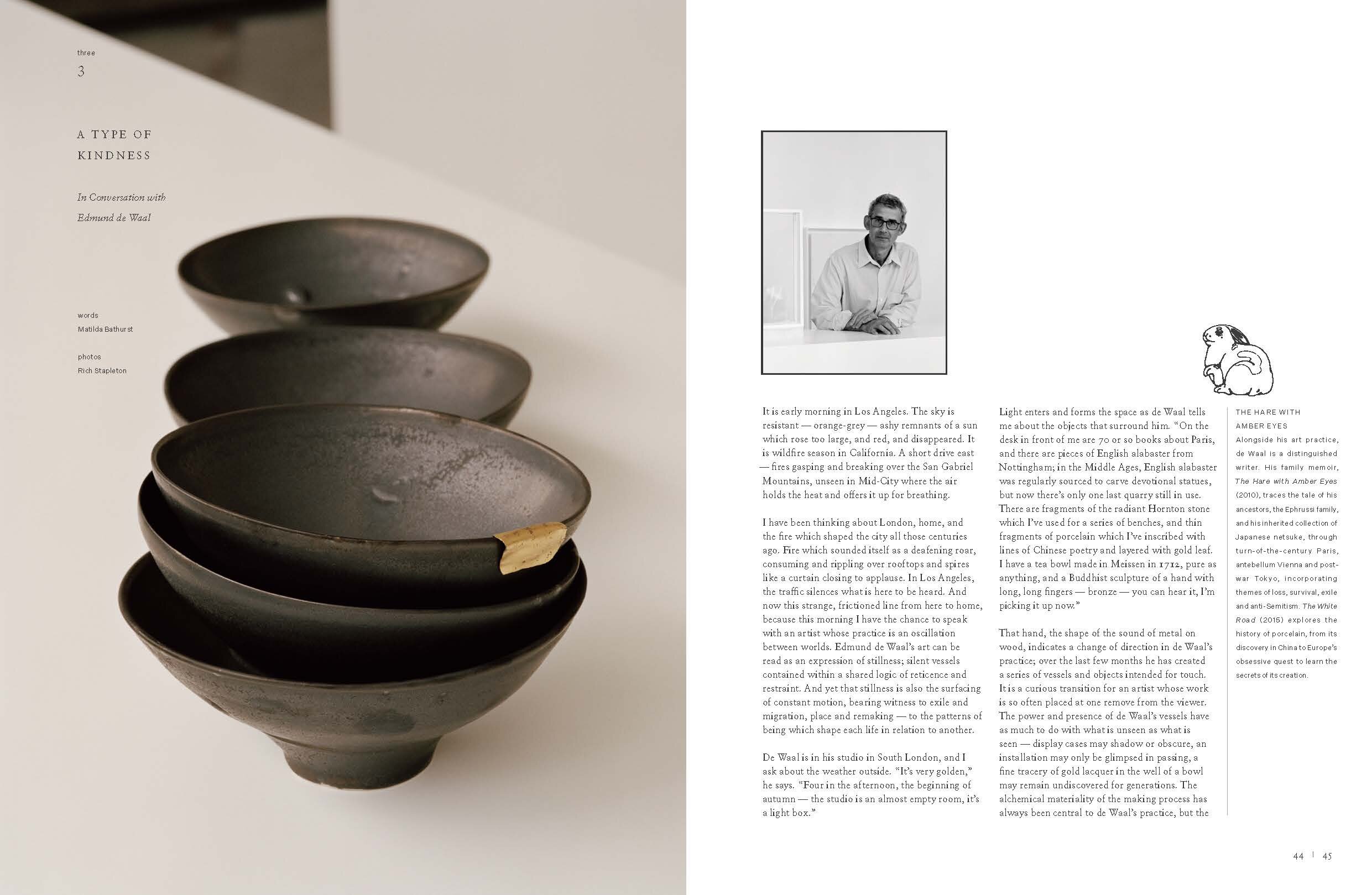

That hand, shaped as the sound of metal on wood, indicates a change of direction in De Waal’s practice; over the last few months he has created a series of vessels and objects intended for touch. It is a curious transition for an artist whose work is so often placed at one remove from the viewer. The power and presence of De Waal’s vessels has as much to do with what is unseen as what is seen – display cases may shadow or obscure, an installation may only be glimpsed in passing, a fine tracery of gold lacquer in the well of a bowl may remain unseen for generations. The alchemical materiality of the making process has always been central to De Waal’s practice, but the instinctual knowledge with arises from handling the finished object – eliminating the distance of desire – is a knowledge itself “withheld.”

“The de-acceleration of quarantine has taken me back to parts of my practice that I thought I’d left behind years ago,” says De Waal. “I’ve found myself making single vessels which aren’t designed to be placed in installations or to relate to each other in any poetic way – they’re simply intended to be held. I have just made a bowl. I glazed it in a very dense black glaze I haven’t used in years. It has a tiny gold fracture on the rim because it was over-fired, and I’m longing for someone to pick it up – it’s gone through that kiln – and the most significant thing for me, at this moment, is to see it in someone else’s hands.“

I am reminded of a line from one of De Waal’s essays: “This holding back is not a retreat from the world.” Words offered freely translate to another’s meaning, and it’s a line which resonates particularly strongly for me in a city which preserves its privacy. Los Angeles — with its car culture and sprawl of single-family homes — is the realisation of a speculator’s fever dream, the promise of a land where each inhabitant could maintain a miniature fiefdom in paradise. That paradox of freedom and entrapment was built into the structure of the city, and it informed the work of the Jewish writers and artists who emigrated to Los Angeles from Europe in the 1920s and 30s – a community whose lives De Waal studied while on residency at the Schindler House in West Hollywood. “I was interested in that idea of beginning again, and what we carry with us from another country,” he says. “The émigrés brought with them their old disgruntlements and sense of status – if you were annoyed with someone in Berlin you would still be annoyed with them in Los Angeles.”

As a storyteller as well as a maker, De Waal is attuned to the brokenness and failures which layer into human culture, the grit which accretes and distills into objects of beauty: netsuke and calligraphy, novels and symphonies. There is something terrifying about the way that life inevitably generates new form – how, by holding to the brokenness, something rises, resolves, and reveals.

That process can only start from where we are – in place, and in time. For me, that is room cast under a sky at remove from fire. For de Waal, it is a studio filled with the light of golden autumn. I cannot elide the spaces into sense. And yet, like gilded kintsugi which draws a line and transforms an object, the making process is its own answer.

“There are forms and materials which seem to work particularly well with fingers and hands and arms and bodies,” says De Waal. “There is a type of kindness – you feel it in the resistance of clay, or the way words are arranged on a page. And then there is the endlessness of the making process itself – it’s iterative, it takes you back – you know you’re not going to run out of clay, you know that the next vessel has to happen, and the vessel after that, and the vessel after that. Making takes you to a space which is not about good conclusions, it’s about positive being.”

Kindness. The materiality of a thing, its supplication to touch. Kindness, the brokenness of a situation, the impossibility of autonomy and the endlessness of agency. Kindness, the forms which rise from reality – the golden mean between fracture and facticity, which is facture. Something which offers itself up to be held – a page, a bowl, a vessel reshaped in the fire of another mind.